Waañ Wi

Waañ Wi takes its name from the Wolof word for kitchen—a space where matter, memory, and relation are continually transformed. In this project, the kitchen is theorized as an epistemic site: a locus of knowledge production grounded in care, repetition, and collective labor. Drawing on bell hooks’ articulation of homeplace as a site of resistance and care, alongside Ken Bugul’s literary practice in Le Baobab Fou, which traces rupture, exile, and return as sources of knowledge, Waañ Wi understands the kitchen not as a private or marginal space, but as a vital arena where survival, dignity, and political imagination are actively produced.

Developed during a residency in Dëkandoo, Senegal, Waañ Wi unfolds through a decolonial methodology of listening. Rather than positioning the artist as a detached observer or extractor of meaning, the project emerges through relational encounters: conversations, shared meals, songs, and material processes. The title itself crystallized through dialogue with Absa Guindo, director of Keru Jigeen Ñi, during a residency in Gandiol. This exchange marked an early displacement of singular authorship, establishing the project as one grounded in feminist collaboration and shared authority.

Archival research at the Documentation Center of Saint-Louis (CRDS), alongside exchanges with photographer Adama Sylla, journalist and cinema critic Baba Diop, and Professor Ibrahima Wane, provided historical and intellectual context. Yet Waañ Wi critically interrogates the archive as an institution—often shaped by colonial logics of selection, omission, and control. In response, the project privileges what both hooks and Bugul articulate in different registers: forms of knowledge that emerge from lived, embodied experience, from intimacy, exile, and return, rather than from institutional validation.

A pivotal moment occurred during a workshop centered on cere mbuum (couscous and moringa), accompanied by the songs of Aminata Fall. In this shared kitchen space, cooking functioned as both material practice and conceptual framework. Echoing hooks’ understanding of homeplace as a site where Black women affirm one another’s humanity, and Bugul’s evocation in Le Baobab Fou of communal spaces as sites of healing and self-reclamation after displacement, the kitchen became a space of mutual recognition, care, and transmission. Here, memory is activated through the body, and cultural knowledge circulates horizontally rather than hierarchically.

Sound operates as a structuring and theoretical force throughout the work. Aminata Fall, who released a single album, Kan Fore, is approached not as an object of representation but as a living archive. Six paintings respond to the album’s six tracks, translating acts of listening into material resonance. One song in particular, Gan, articulates a politics of voice—of speaking for and with one’s community. In dialogue with bell hooks’ notion of talking back and Bugul’s literary practice in Le Baobab Fou, the works do not illustrate this message; instead, they absorb it, allowing rhythm, vibration, and tonal memory to materialize through surface, dye, and gesture.

The making of Waañ Wi is inseparable from processes of co-construction. From the moment Absa Guindo assumed a guiding role—initiating a shift from individual authorship to shared authority—to the dyeing processes led by women who followed their own instincts, cosmologies, and spiritual knowledge, the project resists the modernist myth of the solitary artist. The resulting works bear the traces of multiple temporalities and agencies, aligning with hooks’ ethics of collective care and Bugul’s refusal of linear narratives of identity and belonging, as explored in Le Baobab Fou.

Waañ Wi extends the artist’s ongoing project Forgotten Icons, which reactivates the legacies of figures such as Yandé Codou Sène, Aby Gana Diop, Nina Simone and Lisa Simone, Ama Ata Aidoo, and Oum Kalthoum. Across this lineage, the artist engages with women whose voices have shaped cultural and political consciousness while remaining under-archived or misrecognized. In resonance with Bugul’s autobiographical disruptions in Le Baobab Fou and hooks’ cultural criticism, these figures are approached not as nostalgic symbols, but as theorists in their own right—whose practices continue to inform contemporary modes of resistance, survival, and world-making.

Ultimately, Waañ Wi proposes the kitchen as an archive without walls: a feminist and decolonial homeplace where history is preserved through repetition, resistance through care, and knowledge through relation. In holding bell hooks and Ken Bugul in dialogue, the project insists on theory as something lived, spoken, cooked, sung, and shared—rooted in the everyday practices through which Black women continuously remake the world.

Djibril DRAME

Contributors :

Absa Guindo - Këru Jigeen Ñi

Mani Kallé - Ban ak Suuf

Mamadou Dia / Beleu - Ëttu Gandiol

Maguette Diagne - As Aminata Fall

Seynabou Faye - Documentation

Moussa Boye - Montage son

Massow Ka - Assistant Photo

Laura Feal - Dëkandoo

Amina Niang - As Aminata spectrum

Documentation of the restitution :

Photos : Fatou Kine Diop

Videos : Massow Ka & Seynabou Faye

Dekandoo, Gandiol, Saint Louis, 2025

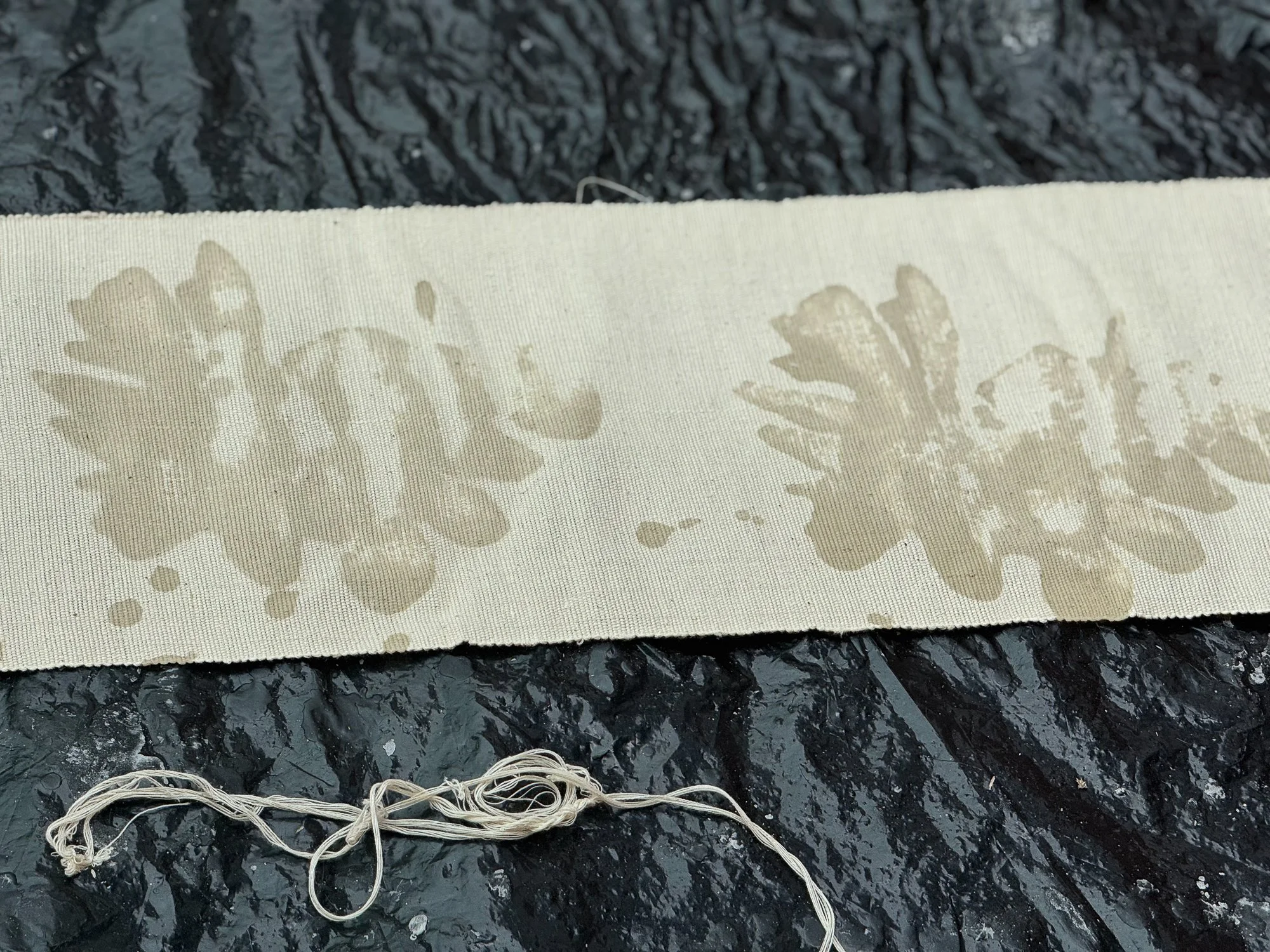

Malaanu Maasla, Local wasted rice bags, hilaires/Moringa figures dyed with hibiscus and indigo pigment on cotton and recycle fish nets from Guet Ndaar, 20 mètres x 40 mètres

COURTESY OF DJIBRIL DRAME

Keru Jigeen Ñi

Photographed by Laura Feal, Seynabou Diop and Fatou Kine Diop women of Keru Jigeen Ñi work at Maalikaan, dyeing fabrics with hilaire and moringa leaves. Sunlight illuminates the cloths as hands fold, press, and submerge them, capturing the rhythm, care, and collective knowledge of this traditional, embodied practice.

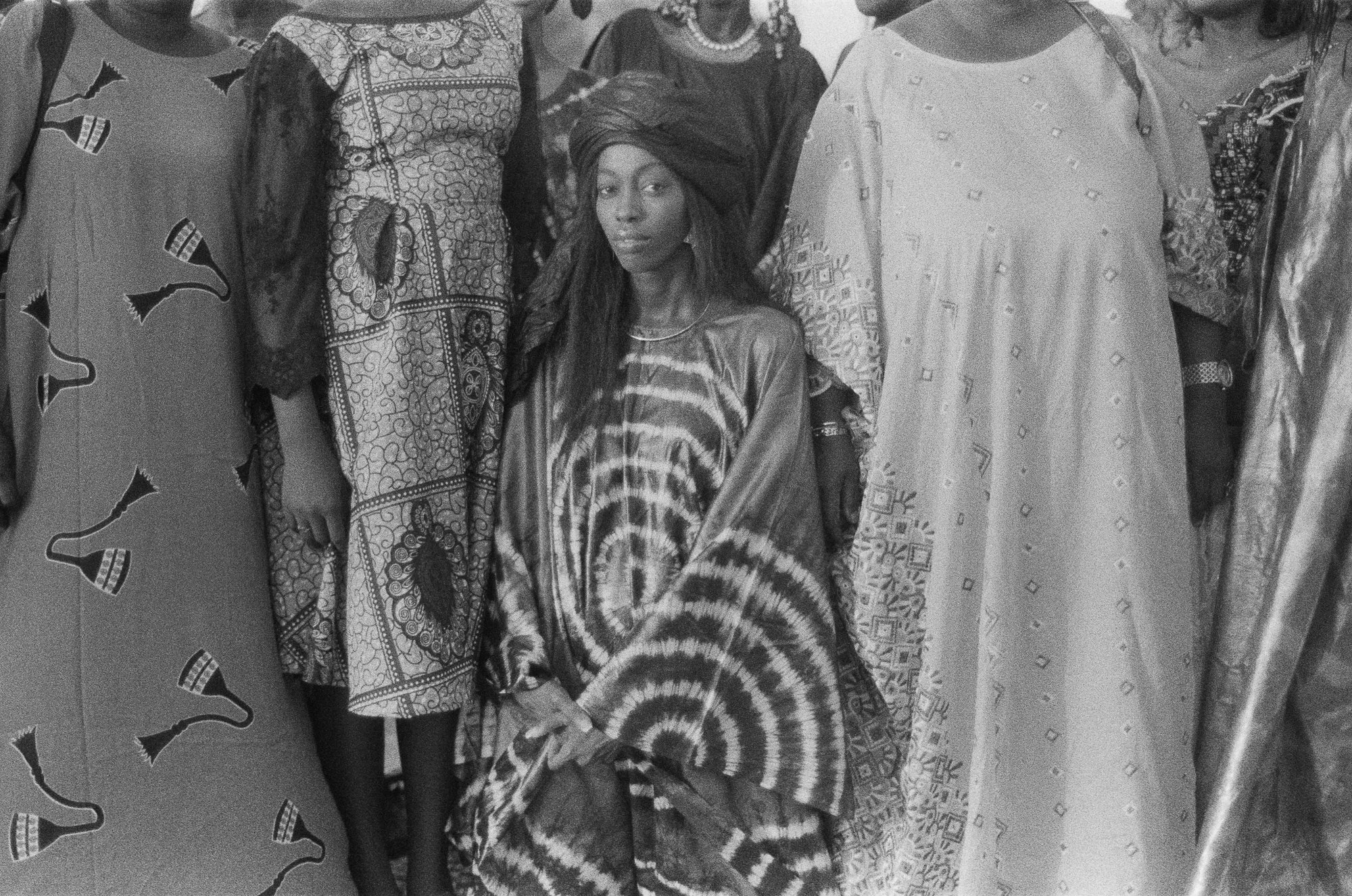

ET SI AMINATA S’eTAIT REINCARNeE ?

WAAÑ WI, PHOTOGRAPHIE ANALOGIQUE SUR NIKON F3, IMPRESSION FINE ART SUR PAPIER HAHNEMÜHLE PHOTO RAG 308G 80 X 120 CM

EDITION 1/3 + 2 ARTIST'S PROOFS

COURTESY OF DJIBRIL DRAME